This is the fourteenth of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to participate in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Bee, which will be held on September 23.

The Seventh Amendment is one of those steady but unspectacular amendments that does not feature prominently in many Supreme Court cases, because it specifies two relatively straightforward rights: (1) trial by jury and (2) finding of facts made by a jury can not be appealed or “re-examined.”

In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury shall be otherwise re-examined in any Court of the United States, than according to the rules of common law.

You may note a phrase in that amendment with which you may not be familiar: “the rules of common law.”

What, exactly, are “the rules of common law,” and what, while we’re at it, do we mean by “common law”?

The Oxford English Dictionary provides the simplest explanation of what is meant by common law: “The part of English law that is derived from custom and judicial precedent rather than statutes. Often contrasted with statutory law.”

The Seventh Amendment continued English traditions in the establishment of what first year students at law school know as civil procedure. It does not apply at all to the other general area of law: criminal procedure.

Here is another important distinction to understand: the difference between civil law and criminal law.

“Criminal law deals with behavior that is or can be construed as an offense against the public, society, or the state—even if the immediate victim is an individual. Examples are murder, assault, theft,and drunken driving,” the Encylopedia Britannica explains.

Civil law deals with behavior that constitutes an injury to an individual or other private party, such as a corporation. Examples are defamation (including libel and slander), breach of contract, negligence resulting in injury or death, and property damage,” the Encylopedia Britannica adds.

“Traditionally, the Supreme Court has treated the Seventh Amendment as preserving the right of trial by jury in civil cases as it ‘existed under the English common law when the amendment was adopted’,” the Legal Information Institute notes.

The Supreme Court added some details to what trial by jury “under the English common law” meant. The jury size could be the traditional “twelve men,” but it could also be as small as six. Of equal importance, in civil trials, the jury verdict must be unanimous, again, as the Legal Information Institute notes:

The right was to “a trial by a jury of twelve men, in the presence and under the superintendence of a judge empowered to instruct them on the law and to advise them on the facts and (except in acquittal of a criminal charge) to set aside their verdict if in his opinion it is against the law or the evidence.” Decision of the jury must be by unanimous verdict. In Colgrove v. Battin, however, the Court by a five–to–four vote held that rules adopted in a federal district court authorizing civil juries composed of six persons were permissible under the Seventh Amendment and congressional enactments.

The first judicial ruling on the Seventh Amendment came in 1812 in a case known as United States v. Wonson, where “the government challenged the accuracy of a jury verdict, and asked the appellate court to reverse the verdict or resubmit the case to a new jury,” as Brandon Boxler wrote in the Richmond Journal of Law and the Public Interest:

Judge [Joseph] Story began his analysis by noting that, “when the constitution was submitted to the people for adoption, one of the most powerful objections urged against it was, that in civil causes it did not secure the trial of facts by a jury.

He reasoned that the Framers passed the Seventh Amendment “to remove the weight of this objection” and prevent judges from intruding—either directly or indirectly—into the province of the jury.

Thus, because he was constitutionally prohibited from reexamining the jury‘s factual determinations, Judge Story denied the government‘s request for relief.

The United States v. Wonson case is a little bit unusual because it established a significant precedent not in a decision made by the Supreme Court, the highest court of the land, but in the Court of Appeals, which is the level of judiciary just below the Supreme Court.

As a reminder, the Constitution authorize Congress to establish the Supreme Court and “inferior” courts.

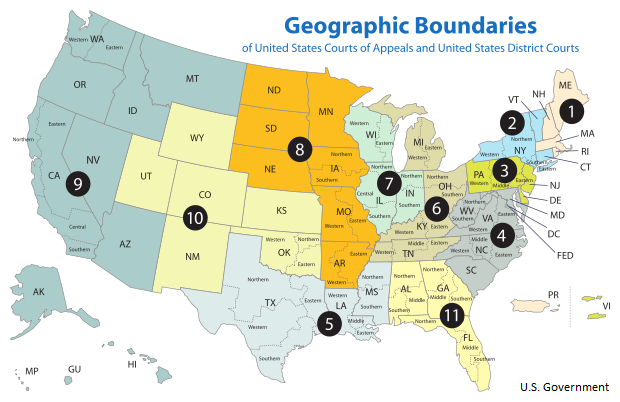

The Judiciary Act of 1789 did that by establishing a number of district courts around the county–where federal cases are initially heard. Litigants who lose at the district court level can appeal to the next level — the Circuit Court of Appeals. There are eleven such Circuit Courts today, divided by geographical region of the country.

Litigants who lose in the Circuit Court have one final appeal–to the Supreme Court.

Since there is no higher court, the Supreme Court decision then becomes the precedent for all of the country to follow.

United States v. Wonson was never appealed to the Supreme Court, in part because the majority decision in the case was written by Associate Justice Joseph Story, who was pulling double duty for a brief time in 1811 and 1812.

He was confirmed as an associate justice of the Supreme Court in September 1811, but issued the United States v. Wonson decision early in 1812 in his capacity as a Court of Appeals judge. He was one of the longest serving members in the history of the Court, serving thirty-three years until his death in 1845.

He is perhaps best known for his majority decision in the famous Amistad case, which was made into a movie by Stephen Spielberg.